Testing the potential risk of developing chronic venous disease: Phleboscore ® - Servier - PhlebolymphologyServier – Phlebolymphology

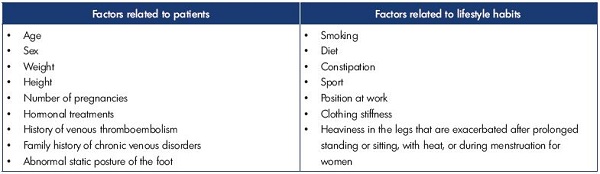

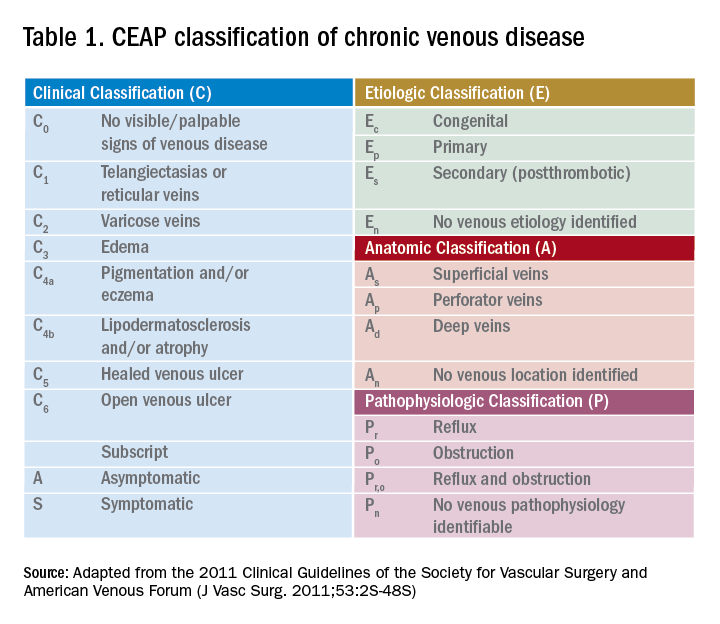

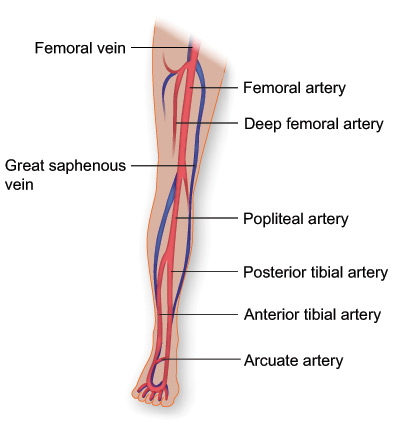

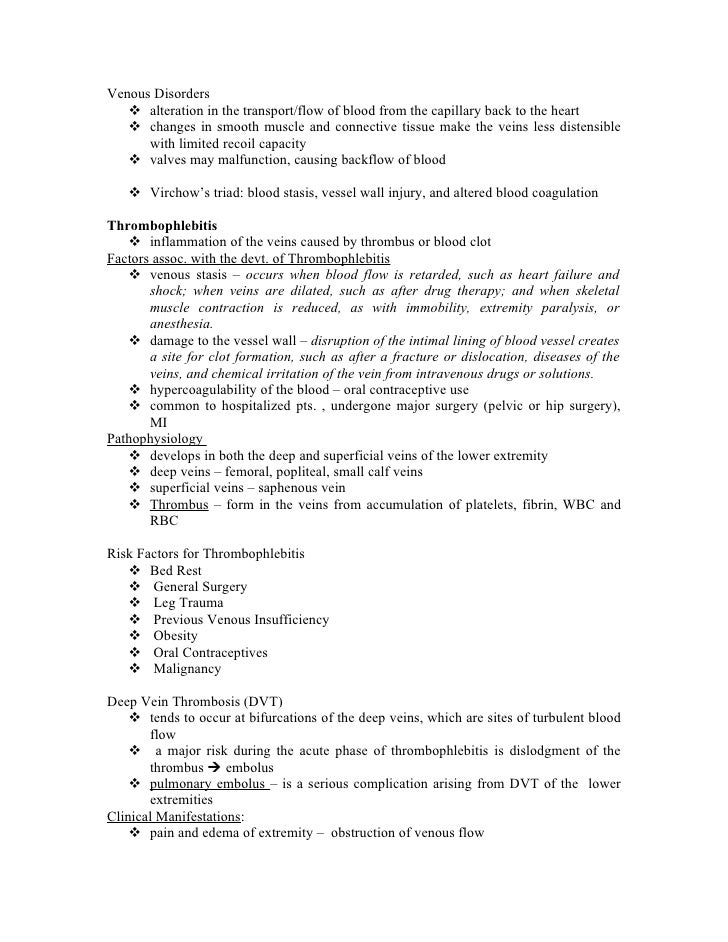

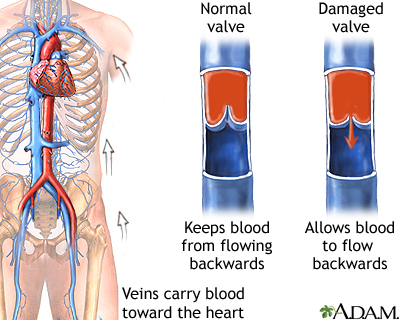

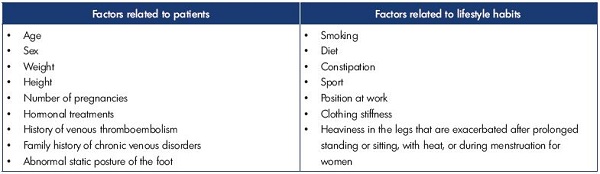

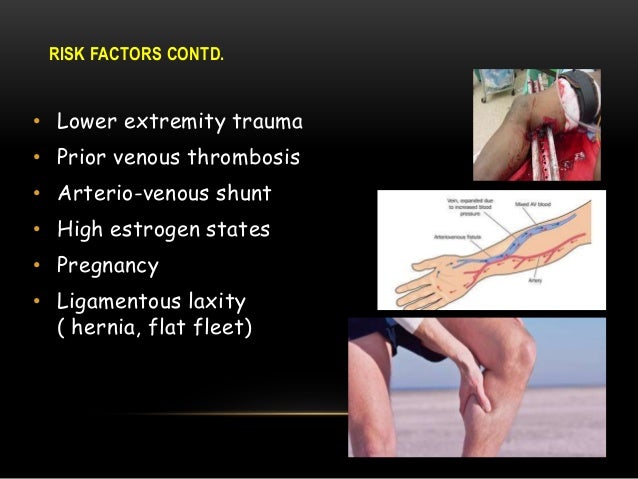

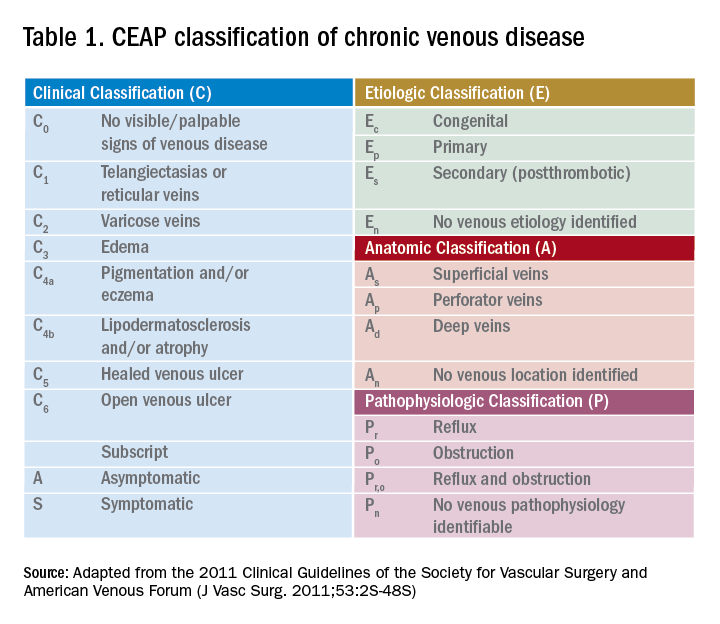

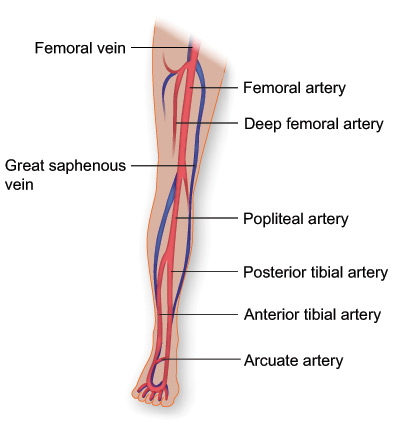

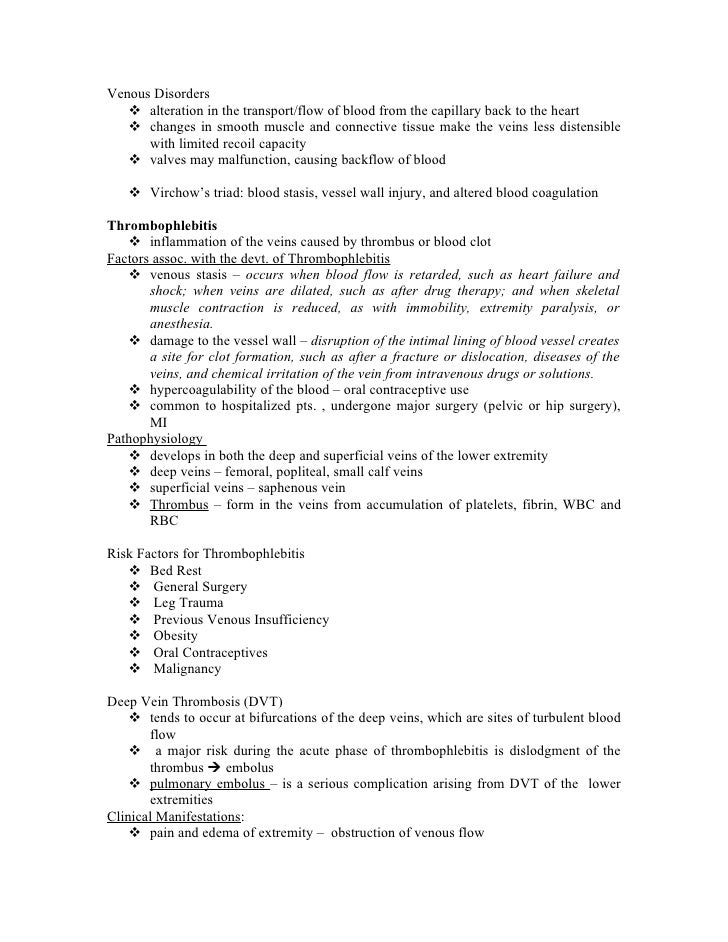

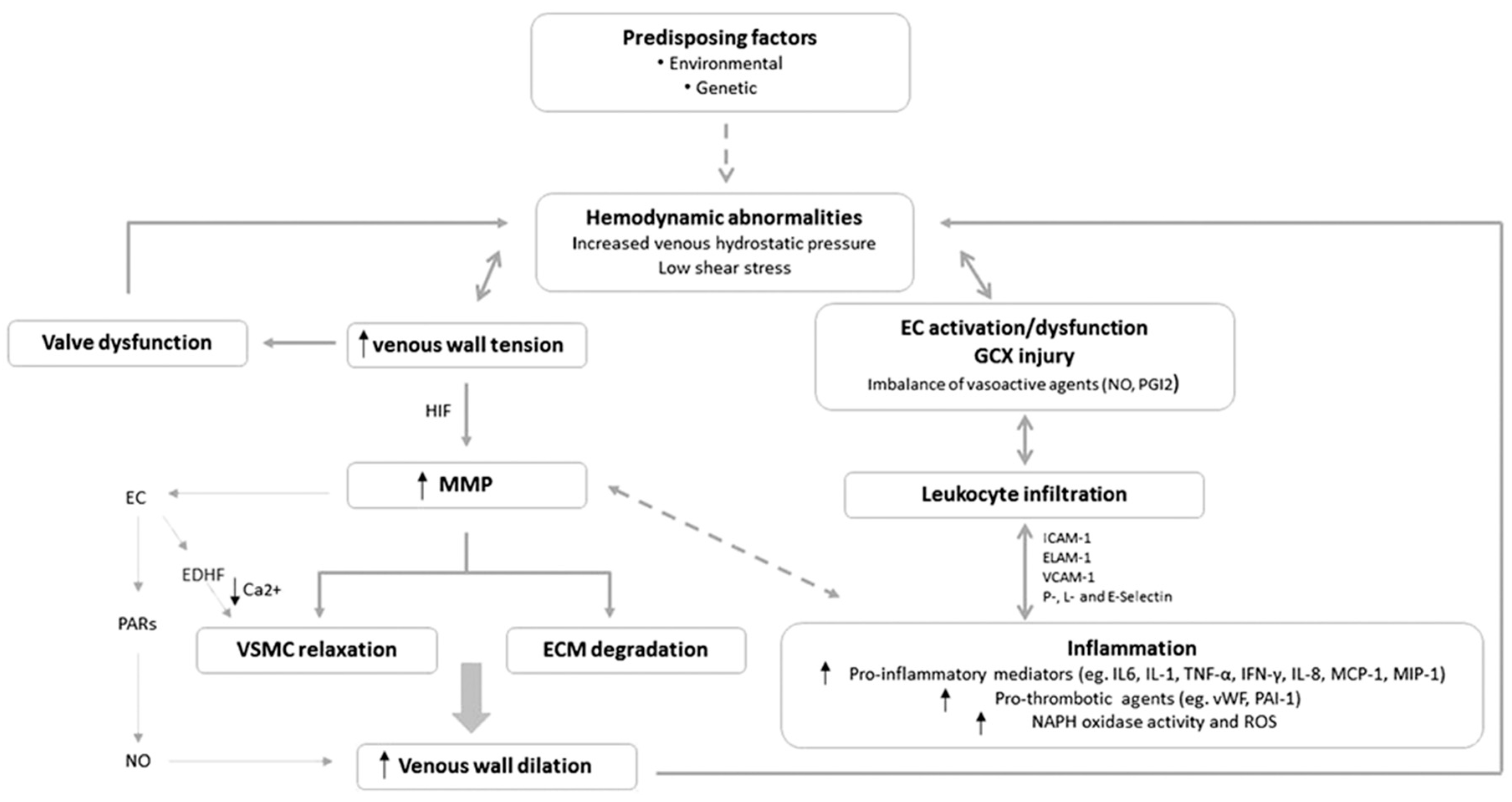

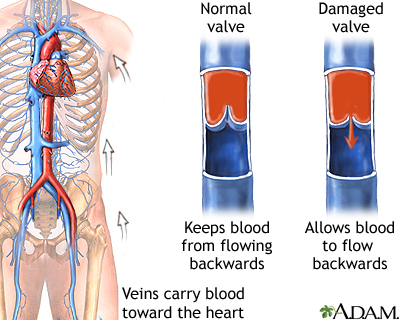

Testing the potential risk of developing chronic venous disease: Phleboscore ® - Servier - PhlebolymphologyServier – PhlebolymphologyWarning: The NCBI website requires JavaScript to operate. Risk Factors for Chronic Veal Disease: San Diego Population StudyMichael H. Criqui1University of California, San Diego, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine2University of California, San Diego, Department of MedicineJulie O. Denenberg1University of California, San Diego, Department of Family and Preventive MedicineJohn Bergan3University of California, San Diego, Department of Medicine The etiology of chronic venous disease in the lower extremities is unclear, and there is very limited data on possible risk factors for representative population studies. MethodsParticipants in the San Diego Population Study, a randomly selected free adult population of age, sex and ethnic strata, were systematically evaluated by risk factors for venous diseases. The categorization of normal, moderate and severe diseases was determined hierarchically through clinical examinations and ultrasound ultrasound ultrasound ultrasound ultrasounds by trained vascular technologists, which also carried out anthropometric measures. An interviewer administered questionnaires and examined possible risk factors for venous diseases suggested in previous reports. ResultsIn multivariate models, moderate venous disease was independently related to age, family history of venous disease, hernia pre-surgery surgery and normotension in both sexes. In men, the current walk, the absence of cardiovascular disease, and not moving after sitting were also predictive, while in women, the additional predictors were weight, number of births, oophorectomy, flat feet, and not sitting. For severe diseases, age, family history of venous disease, waist circumference and flat feet were predictive in both sexes. In men, occupation as a worker, tobacco and normmotension were also independently associated with serious venous diseases, while in women there were additional significant and independent predictors, history of leg injury, number of births and cardiovascular diseases, while the African-American ethnic group was protective. Many other postulate risk factors for venous disease were not significant in multivariate analysis in this population. Conclusions Although some risk factors for venous diseases such as age, the family history of venous disease, and the suggestive findings of ligamentous laxity (hernia surgery, flat feet) are immutable, others can be modified, such as weight, physical activity and cigarette. In general, this data provides modest support to the potential for changing behavioral risk factors to prevent chronic venous diseases. Abnormalities of veins in the lower extremities are responsible for significant and widespread morbidity. The prevalence of venous diseases increases with age () and an ageing world population is likely to lead to increased venous disease. However, chronic venous disease etiology is misunderstood and only a limited number of potential risk factors have been explored, some with contradictory results. A recent review () showed that there are many hypotheses concerning the development of varicose veins, chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) and venous ulcers. This last final point has been the most explored in previous studies, but it is less common than other manifestations. In the San Diego Population Study (SDPS), we systematically examine the relationship of a wide variety of potential risk factors for visible and functional venous diseases. Risk factors considered include family history (-), connective tissue laxity (-), anterior trauma of the lower extremity (, ), factors related to cardiovascular disease (, ), position factors (-), physical measures (-), smoking (), constrictive clothing (-), a period of immobility (), physical activity (, ), constipation (-), fiber ingestion (, ) and hormonal factors (-). This is a report of our conclusions. MATERIALS AND METHODology The population for this study was randomly selected from current and retired employees at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). Random selection was performed within the strata defined by age, sex and ethnicity. The categories from 40 to 49 years, from 50 to 59 years, from 60 to 69 years and from 70 to 79 years of age define age strata. Women were superselected to allow for additional power for certain specific female hypotheses. Ethnic minorities—Hispanic, African American and Asian—were superselected to allow the statistical power of ethnic contrasts. The spouse or randomly selected participant were also invited to participate in the study. Some volunteers (n=199) who had heard of the study and asked to participate were registered. By selecting people from all levels of education and occupation, and both workers and retirees, we were able to study a wide-based population sample. For all study procedures, participants provided signed informed consent after a detailed introduction to the study. The study was approved by the UCSD Human Issues Research Committee and all participants gave their informed voluntary consent. Registered vascular technicians were trained and monitored for each component of the study visit. Particular attention was paid to the close adherence to the study protocol, which specifically defines the criteria for each of the venous conditions. Details of the protocol (). Classification of diseases In previous SDPS reports we characterize each participant's leg separately by four categories of visible disease; normal, webidectsis or spider veins, varicose veins or trophic changes, and by three categories based on duplex ultrasound assessment; normal functional, superficial or deep functional disease (). Due to the large number of risk factors assessed, for the simplicity of each leg for this report were classified into three general categories, mutually exclusive, heiracic, normal, moderate or severe disease, as described below. Normal people without varicose veins, without tropical changes (lipowermatosclerosis, hyperpigmentation, cured ulcer or active ulcer in visual inspection) and without insufficiency or obstruction of deep or superficial systems in ultrasound duplex inspection were classified as "normal". This corresponds to C0 or C1 with Pn in the revised classification CEAP (). Moderate Venous Disease People with varicose veins or reticular varicose varicose veins in the absence of trophic changes in visual inspection, or with insufficiency or obstruction of the surface system or perforating veins, but not in the deep system by duplex ultrasound were classified as a moderate disease. The graves with a history of venous dispossession in the absence of severe illness were classified as moderate. This corresponds to C2 or As or Ap in the revised classification CEAP (). Severe Venous Disease People with trophic changes in visual inspection or insufficiency or obstruction in the deep system by duplex ultrasound were classified as serious diseases for this report. This corresponds to C4 or C5 or C6 or Ad in the revised CEAP (). Risk Factors In the study visit, trained interviewers followed a standardized protocol to obtain information about demography, lifestyle and personal and family medical history. Vascular technologists evaluated anthropometric measures. Ethnicity and Occupation Subjects define their race/ethnicity as: "Well, not Hispanic", "Hispanic/Chicano", "African American", "Asian/Pacific Islander", "Native American", or "Other". The current occupation of the subject (or the last occupation if removed), was classified by the interviewer as "professional", "technical/administrative/managerial", "clerical/skilled", "semi-skilled", or "laborer". Personal Habits Estimated hours spent lying, sitting, walking and standing, currently and as adults. The subjects answered whether when they sat for long periods they regularly rose to move today and as adults. The history of the use of constrictive clothing, including gins, corsets, abdominal braces and exercise dress, was evaluated. The subjects assessed their level of physical activity in relation to the people of their age. The subjects calculated how many times they were engaged in vigorous activities (with a higher heart rate) for at least 20 minutes a week. Smoking history, including current and average daily intake of cigarettes and smoked years was evaluated. Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle WA ( analyzes standardized self-administered dietary evaluation forms. History of health History of the cardiovascular health of the subjects, the history of high blood pressure and diabetes was checked. Questions were asked about immobility and intestinal activity. Serious injuries were determined in the lower extremities. The history of the subjects of hernia surgery, diverticulosis, diverticulitis and abnormalities of the veins of non-lower members was evaluated. Women were asked about their reproductive history. Self-reported topics if they had hypermobile joints and flat feet. Family History The family history (all first-degree relatives) of telangiectasis, varicose veins, blood clots in lower-extreme veins, flebitis, venous ulcer, pulmonary embolism or other venous problems were evaluated. Anthropometry The height, weight, heart rate, waist and hip circumferences were measured. Blood pressures were measured in the right arm after the subject had been sitting quietly for five minutes. The foot-foot height was visually classified as flat, small or normal/high. Quality Control In a standardized manner, interviewers were trained to administer the questionnaire protocol, and vascular technologists were trained in physical examination and duplex ultrasound protocol, with periodic evaluation for quality control. Reliability data have been published (). All numerical variables introduced in the Microsoft Access database had range checks. A random sample of 2% was further checked against the chart, and the outliers were also systematically revised for each individual variable against the chart. Statistical Analysis All analysis was performed using SAS 8.1 for Windows (). Univariate analysis adjusted by age and all multivariate analysis used logistical regression. The multivariate analysis used the p0.10 input criteria for gradual logistic regression to develop the final models. Age variables and indicators of ethnic origin were included in all models. RESULTS The study population consisted of 854 men and 1580 women of average ages (standard deviation) of 60.1 (11.4) and 58.8 (11.4) respectively. Ethnic distribution was approximately 60 percent non-Hispanic white (NHW), 15 percent Hispanic, 13 percent African American and 12 percent Asian. We have previously published the relationship of venous disease by sex, age and ethnicity in the study population (). shows the distributions of percentages specific to the sex of moderate and severe diseases in SDPS by age and ethnicity. Moderate and severe venous disease increased with age. Women have almost twice the rate of moderate disease that men have, while men have higher rates of severe disease. The distribution of the disease was significantly different for men and women (population of the 4th 1 Demographic Distribution of Venous Disease by Age, Sex and EthnicityMEN, %WOMEN, %AGENNLMODSEVNNLMODSEV* Some percentages do not amount to 100 per round. Abbreviations: N=number, NL=normal, MOD=moderate, SEV=severe, ETHN=ethnicity, NHW=No-Hispanic White, Hisp=Hispanic, Af-Am=African American shows the distribution of risk factors by category of venous disease —Normal, Moderate or Severe — and by sex. These variables were selected from a long list of potential risk factors because each showed univary relationships with moderate or severe venous disease. This was included in the multivariate logistical regression models discussed below. Variables that did not show univary associations included multiple dietary factors such as fiber intake, intestinal habits and gastrointestinal problems, regular physical activity and constrictive clothing. % of the patient's body. Moderate venous disease Table 3 Risk factors for moderate venous disease (vs. Normal) in men and women (variable income in model 0.3, output 0.1)MenWomenVariablePoint estimate95% CI*Point estimate95% CI*Age (10 years)1.591.26, 2.001.431.25, 1.64African-American0.640.25, 1.600.840.571.85 History0.220.08, 0.66--------Curr. Move After Sitting0.310.13, 0.79------Adult Sitting (per hour)--------------0.920.87, 0.96Weight (10 kilograms)---------1.321.12, 1.56Number of birthsnana1.141.05, 1.23Water circle (10 cm)--------------0.830.69, 1.00Oophorectom. Dis. = history of venous disease, CVD=cardiovascular disease, Curr=currently, Circumf.=circumference, na=not applicable Four variables were very significant for moderate disease in men and women in multivariate analysis; age, family history of venous disease, prior hernia surgery and hypertension. The probability rates (OR) for age (per decade) were 1.59 in men and 1.43 in women; for family history, 2.87 and 2.34 respectively, and for hernia surgery 1.85 and 1.81 respectively. Hypertension showed an inverse relationship, with probabilities ratios of 0.58 and 0.64 respectively. All confidence intervals for these associations excluded the null hypothesis. Although moderate disease, compared to NHW, was greater in Hispanics and less in African Americans and Asians, none of these associations reached statistical significance. Additional significant predictors in men, by order of statistical significance, were to walk (by hour), OR = 1.14; CVD history, OR = 0.22; and a protective association for the current movement after sitting for long periods, OR = 0.31. In women, the additional predictors in order of statistical significance were adult life sitting (per hour), OR = 0.92; weight (per 10 kilograms) OR = 1.32; birth number (by birth), OR = 1.14; waist circumference (per 10 cm), OR = 0.83; previous oophorectomy, OR = 1.37; and flat feet, OR = 1.39. Serious Venous Disease Table 4 Risk Factors for Serious Venous Disease (vs. Normal) in Men and Women (multi-tivatable intake in model 0.3, output 0.1)MenWomenVariablePoint estimate95% CI*Point estimate95% CI*Age (10 years)1.411.17, 1.701.431.21, 1.68African-American0.630 1.350.440.26, 0.7790 Family. Dis.2.131.44, 3.161.921.33, 2.77Waist Circumf.(10 cm)1.371.15, 1.631.241.11, 1.39Laborer3.241.21, 8.67------Dias. BP (10 mm/Hg)0.800.67, 0.97... Current Cigs. (20/day)2.241.11, 4.54------------Flat Feet1.630.97, 2.75------------ Flat arch (normal vs)--------3.281.83, 5.89Current Stand. (per hr)------1.141.05, 1.24Small Arch (normal vs)-------1.841.25, 2.71Leg Injuries-------1.671.14, 2.44Number of birthsnana1.141.03, 1.27CVD History-----2.021 Dis. = history of venous disease, Circumf.=circumference, Dias. BP=diastolic blood pressure, Cigs.=cigarettes, Stand.=standing, CVD=cardiovascular disease, na=not applicable Three variables were very significant for both men and women in multivariate analysis; age, family history of venous disease, and waist circumference. RWs in men and women respectively were 1.41 and 1.43 in age; 2.13 and 1.92 in family history, and 1.37 and 1.24 in waist circumference. The only significant association for ethnicity was a reduction in the likelihood of serious illness in African American women, OR = 0.44. Data for men of African-American ethnic origin were also suggestive (OR = 0.63), but the confidence interval included one. Additional significant predictors in men, by order of statistical significance, were occupation as a worker, OR = 3.24; diastolic blood pressure (for 10 mm/Hg), OR 0.80; current cigarettes per day (for 20 cigarettes), OR = 2.24; and flat feet, OR = 1.63. In women, the additional predictors by order of statistical significance were flat (OR = 3.28) or small (OR = 1.84) arc standing; current position (per hour), OR = 1.14; previous leg injury, OR = 1.67; birth number (by birth), OR = 1.14 and CVD history, OR = 2.02.DISCUSSIONAging, sex and ethnic origin were important risk factors for the disease of the previous. Our results confirm that older age is a risk factor for venous disease. They also did not show significant ethnic differences for moderate disease, but a significantly less severe disease can be more common in African American women. Family history was a risk factor for moderate and severe diseases. Many studies have found an association with family history and venous disease (-), although not all (, ). As other researchers have pointed out, the biased memory could have influenced this finding (, ). However, in our study, the family history based on the topic recalls was a very strong risk factor for venous disease. In addition, it shows subjects without venous disease reported high family history rates of venous disease. Laxity of the connective tissue, as manifested in hernia prior surgery or in the findings of the flat feet, was a consistent risk factor for both moderate and severe diseases. The association of growing laxity in connective tissue with venous disease corroborated the previous research (-). Pre-hernia surgery may have been a pre-hospitalization and immobility marker. However, this last variable was not significantly associated with venous disease in our data. The injury to the lower extremity is a risk factor in women for serious illnesses. This finding corresponds to the results of Bermudez et al. , who noted that insufficiency in deep veins increased in members who had been traumatized compared to the limbs they did not have (). Similarly, a case-control study found a lower severe trauma to the limbs as a risk factor for CVI (). However, an earlier study found no difference in CVI for injured members against uninjured members (). Factors related to CVD, specifically hypertension, previous CVD and higher diastolic blood pressure were associated with a less moderate disease for men and women and a less severe disease for men. On the contrary, a CVD story was strongly associated with severe disease in women. Although some studies have found a relationship between atherosclerosis and venous disease (, ), others do not have (). The reason for any protective effect of atherosclerosis in moderate or severe venous disease is not easily evident, although relative arterial insufficiency, venous vasoconstriction and microtrombosis may be involved. Position factors such as walking, standing and sitting showed variable associations with venous disease. In women, the increase in time was positively associated with a more severe disease, and the time of seated inversely associated with moderate disease increased. For men, the increase in the daily hike was associated with moderate disease, and men who worked as workers were more likely to have a serious illness than those in positions that normally require more desktop time. The regular movement when sitting for long periods was related to lower rates of moderate disease in men. Fowkes et al. It was also found that the seated was associated with lower rates of venous insufficiency for women and not for men (). Fowkes et al. He also found that walking was a risk factor for women with venous insufficiency when the age was adjusted, but less when it multiplied. They found that walking was related to the lower risk of venous insufficiency in men (). Our data indicate that the position was a strong risk factor for serious venous diseases in women. This is consistent with several studies (, , , , -) and contrasts with some other studies (, , , , ). Our finding that moving in if sitting for long periods of time was related to lower rates of moderate disease for men coincides with the hydrostatic model of venous disease. That is, while sitting and lying are usually more protective than walking or standing, there is still the possibility of a little blood seal during the previous activities. Moving around could activate the venous pump and avoid such watering. Physical measures are risk factors for women with severe and moderate illnesses and men with serious illnesses. Weight and waist circumference are both adiposity measures. Several studies have found an association of obesity with venous disease. Both Sisto and others () and Gourgou and others () found a relationship both in men and in women with varicose veins; and Widmer and Abramson et al. both found an association for women (, ), and Beaglehole found an association for men (). Our finding of the greatest circumference of the waist in both sexes with severe disease was consistent with Scott's conclusions that obesity was associated with CVI and with Mota-Capitao et al.'s finding that the weight was an independent risk factor for CVI in multivariate analysis (, ). In contrast, Coughlin et al. and Fowkes et al. Both found that obesity was not a factor of venous insufficiency among women (, ). spread this finding to men too (). Other studies have also not found association between obesity and venous disease (, , -). However, the Edinburgh group also found that for men and women combined, people with more segments with reflux had body mass indices higher than those with less or no segment involved (). Hormonal factors in women, the number of births and oophorectomy are related to moderate or severe venous diseases. Gourgou et al. and Laurikka et al. found a growing prevalence of varicose veins with a growing number of births (, ). He discovered that multiparity was associated with varicose veins in pregnant women (), as did Sisto et al., Maffei et al. and Sohn et al. (, , ) Some studies have found that changes occur with a single pregnancy (, , , , ). In Guberan et al. and Lee et al., pregnancy was no longer a risk factor once the data had been adjusted (, ). In two studies, Sparey et al. evaluated women with and without varicose veins at the beginning of pregnancy (, ). While none of the groups developed new varicose veins during pregnancy, both had dilation of veins during pregnancy and, in women without varicose veins, the diameter had not returned to the reference size in 6 weeks after delivery. Smoking partnered with higher rates of serious illness for men. One study has shown that VV partnered with a larger number of smoked cigarettes per day (), but this is the first report of a sex-specific association limited to severe venous diseases. Constrictive clothing, immobility, exercise, constipation and dietary fiber were not risk factors for moderate or severe diseases in multivariate models. Several questions addressed each of these five categories of potential risk factors, but none were statistically significant in multivariate analysis. Thus, despite the biological plausibility of these factors and some previous reports, this comprehensive population-based study did not confirm the importance of such factors in peripheral chronic venous disease. The limitations of these results include cross-sectional study design, where correlations do not necessarily imply causality. In addition, some of the risk factors examined were self-reported and there was no formal validation of the responses of the subjects. A specific concern in this area was the strong and independent association of a family history of venous diseases for both men and women and for moderate and severe diseases, which could to some extent reflect the recalled bias. However, about half of the participants with normal veins reported a family history of venous disease, so this report was common in those with and without venous disease. CONCLUSIONThis comprehensive cross-sectional study of venous disease helps to clarify contributions from a variety of risk factors to moderate and severe venous disease. Our data indicate that age, family history and ligamentous laxity were the strongest and most consistent risk factors for venous disease. None of these conditions are susceptible to intervention, so these findings have little involvement in disease prevention. Factors related to CVD were generally associated with lower rates of venous disease. However, several behavioral and environmental factors showed significant relationships. Among the voltage factors were important findings: central adiposity, positional factors such as the hours spent standing or sitting, smoking cigarettes and parity in women, and all but the last variable is reasonably subject to intervention. In addition, preventing obesity and smoking or intervention in cigarettes would also benefit from conditions such as CVD and cancer. In women (but not in men) we confirm the importance of an earlier injury of the lower limb due to serious illness. These data provide modest support for the potential for changing the behavioral risk factor to prevent chronic venous diseases. Incidence studies would provide greater understanding of the role of risk factors in the development and progression of moderate and severe venous diseases. Acknowledgements This research was supported by National Institutes of Health – National Heart, Pulmonary and Scholarship of the Blood Institute 53487 and National Institutes of Health of the General Center for Clinical Health Research, MO1 RR0827. Abbreviations Page Footnotes Disclaimer from the editor: This is a PDF file from an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will be submitted to copy, composition and revision of the resulting test before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process you can discover errors that could affect the content, and all legal claims that apply to the journal. ReferencesFormats: Share , 8600 Rockville Pike, Bethesda MD, 20894 USA

Prevalence, risk factors and clinical patterns of chronic venous disorders of the lower extremities: Population study in FranceObjectives The objectives of this study were to document the prevalence of varicose veins, skin morphic changes and venous symptoms in a sample of the general population of France, to document their main risk factors and to evaluate relationships between them. MethodsThis cross-sectional epidemiological study was carried out in the general population of 4 locations in France: Tarentaise, Grenoble, Nyons and Toulon. Random samples of 2000 by location were interviewed by telephone, and a sub-sample of subjects interviewed by doctors and subjected to physical examinations, and the presence of varicose veins, trophic changes and venous symptoms were recorded. ResultsThe prevalence of varicose veins, throphic skin changes and venous symptoms was not statistically different in the 4 places. On the other hand, differences related to sex were found: varicose veins were found in 50.5% of women compared to 30.1% of men (ConclusionPOur results show a high prevalence of chronic venous disorders of the lower extremities in the general population of France, without significant geographical variations. They also provide interesting information about the association of varicose veins, skintrophic changes and venous symptoms. With the support of Grant AR-31283 of the National Institute of Artistic and Musculoskeletal Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and Joseph Fourier University of Grenoble, France. Competition of interest: none. Recommended articles Cite articles Metrics of the article We use cookies to help provide and improve our service and personalized content and ads. By continuing to accept . Copyright © 2021 Elsevier B.V. or its licensors or collaborators. Direct Science ® is a registered trademark of Elsevier B.V.ScienceDirect ® is a registered trademark of Elsevier B.V.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/venuous-insufficiency-overview-4177929-v1-5c3b9644c9e77c0001c7fd3a.png)

Venuous Insufficiency: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment

Lower Extremity Venous Disease: Peripheral Venous Insufficiency - ppt video online download

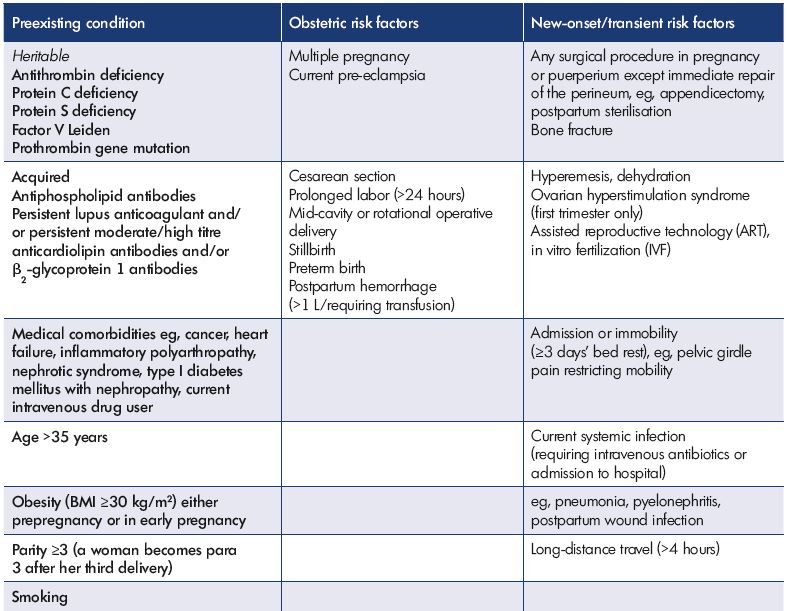

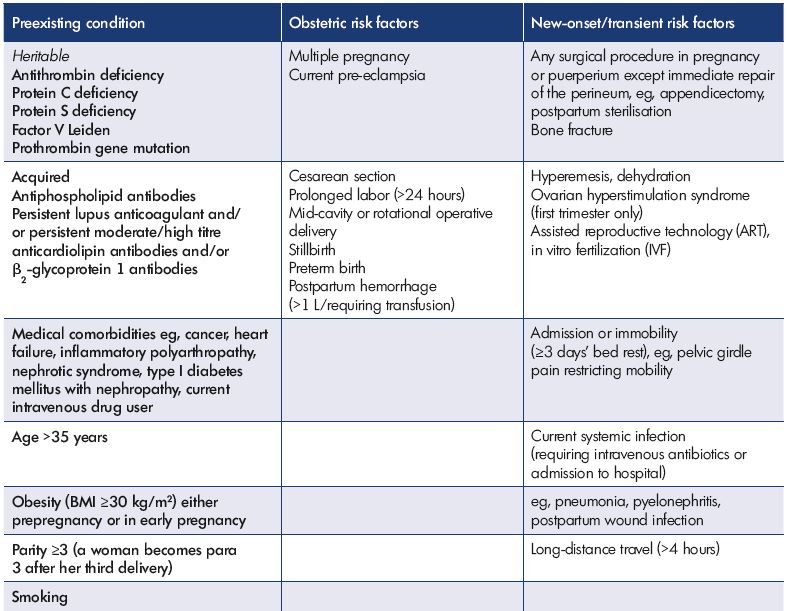

Prevention and treatment of venous disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period - Servier - PhlebolymphologyServier – Phlebolymphology

Chronic Superficial Venous insufficiency

Underlying peripheral arterial or venous disease in patients with lower extremity SSTIs | The Hospitalist

PPT - CHRONIC VENOUS INSUFFICIENCY (CVI) PowerPoint Presentation, free download - ID:6676136![Treatment options for common leg ulcers [25, 26]. | Download Table Treatment options for common leg ulcers [25, 26]. | Download Table](https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Shubhangi-Agale/publication/258393549/figure/tbl4/AS:670720275263515@1536923583849/Treatment-options-for-common-leg-ulcers-25-26.png)

Treatment options for common leg ulcers [25, 26]. | Download Table

Evaluation and Management of Lower-Extremity Ulcers | NEJM

Chronic venous insufficiency - Wikipedia

Venous leg ulcer prevention 1: identifying patients who are at risk | Nursing Times

Chronic Venous Disease: Beyond Blood Thinners & Stockings | Texas Heart Institute

Venous vs. Arterial Lower Extremity Ulcers: Differential Diagnosis and Interventions | WoundSource

Deep vein thrombosis - Wikipedia

Vein Disorder

Compression for Primary Prevention, Treatment, and Prevention of Recurrence of Venous Leg Ulcers: An Evidence-and Consensus-Based Algorithm for Care Across the Continuum. - Abstract - Europe PMC

10 home remedies for varicose veins

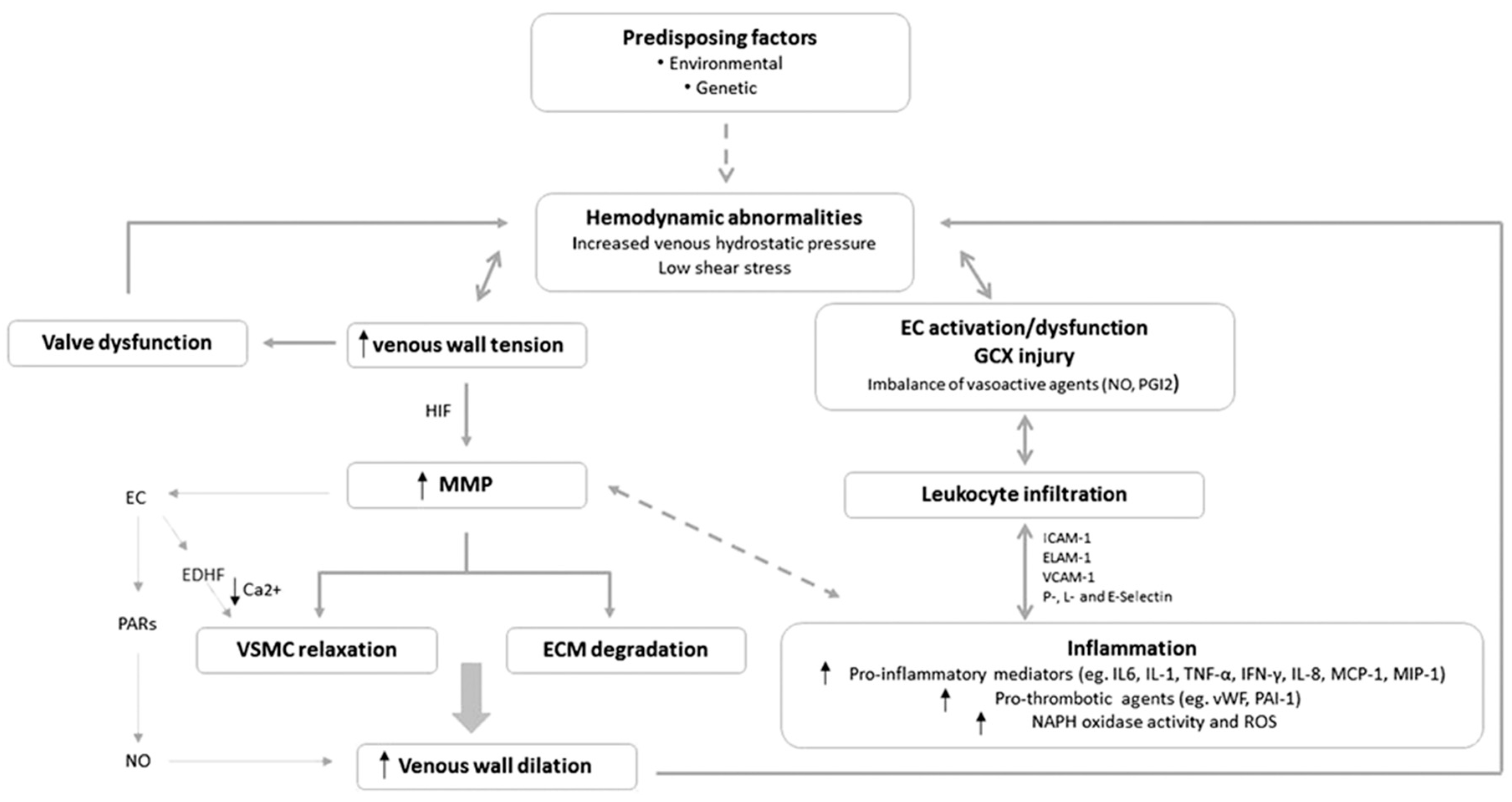

IJMS | Free Full-Text | Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Chronic Venous Disease and Implications for Venoactive Drug Therapy | HTML

Editor's Choice – Management of Chronic Venous Disease - European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Vascular system 3: diseases affecting the venous system | Nursing Times

Department of Surgery - Chronic Venous Insufficiency

Venous insufficiency: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia

Chronic Venous Insufficiency | Circulation

The 2020 appropriate use criteria for chronic lower extremity venous disease of the American Venous Forum, the Society for Vascular Surgery, the American Vein and Lymphatic Society, and the Society of Interventional![PDF] Lower Extremity Venous Disease | Semantic Scholar PDF] Lower Extremity Venous Disease | Semantic Scholar](https://d3i71xaburhd42.cloudfront.net/f5f932004ee365bcb8119cca9315907c1dc7353c/2-Table29-1-1.png)

PDF] Lower Extremity Venous Disease | Semantic Scholar

Deep Venous Insufficiency - TeachMeSurgery

Global, regional, and national prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2015: an updated systematic review and analysis - The Lancet Global Health

Varicose Veins - Cardiovascular Disorders - MSD Manual Professional Edition

Chronic venous insufficiency – a review of pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment - Santler - 2017 - JDDG: Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft - Wiley Online Library

Chronic Venous Insufficiency: Treatment, Symptoms & Causes

Chronic Venous Insufficiency: Know What to Look for - and How It's Diagnosed - RAI Health & Awareness Blog

Protocol for a longitudinal cohort study: determination of risk factors for the development of first venous leg ulcer in people with chronic venous insufficiency, the VEINS (venous insufficiency in South Florida) cohort |

Lower extremity arterial disease in patients with diabetes: a contemporary narrative review | Cardiovascular Diabetology | Full Text

Vascular Diseases_CJ. | Varicose Veins | Vein

Chronic Venous Insufficiency | Johns Hopkins Medicine

Classification of Venous Disease | Allure Medical

Incidence and Risk Factors for Venous Reflux in the General Population: Edinburgh Vein Study - ScienceDirect

Peripheral Arterial Disease - Physiopedia

Chronic Venous Disease: Beyond Blood Thinners & Stockings | Texas Heart Institute

Chronic venous disease - AMBOSS

Chronic Venous Insufficiency | Circulation

Testing the potential risk of developing chronic venous disease: Phleboscore ® - Servier - PhlebolymphologyServier – Phlebolymphology

Testing the potential risk of developing chronic venous disease: Phleboscore ® - Servier - PhlebolymphologyServier – Phlebolymphology:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/venuous-insufficiency-overview-4177929-v1-5c3b9644c9e77c0001c7fd3a.png)

![Treatment options for common leg ulcers [25, 26]. | Download Table Treatment options for common leg ulcers [25, 26]. | Download Table](https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Shubhangi-Agale/publication/258393549/figure/tbl4/AS:670720275263515@1536923583849/Treatment-options-for-common-leg-ulcers-25-26.png)

![PDF] Lower Extremity Venous Disease | Semantic Scholar PDF] Lower Extremity Venous Disease | Semantic Scholar](https://d3i71xaburhd42.cloudfront.net/f5f932004ee365bcb8119cca9315907c1dc7353c/2-Table29-1-1.png)

Posting Komentar untuk "which is a risk factor for venous disorders of the lower extremities?"